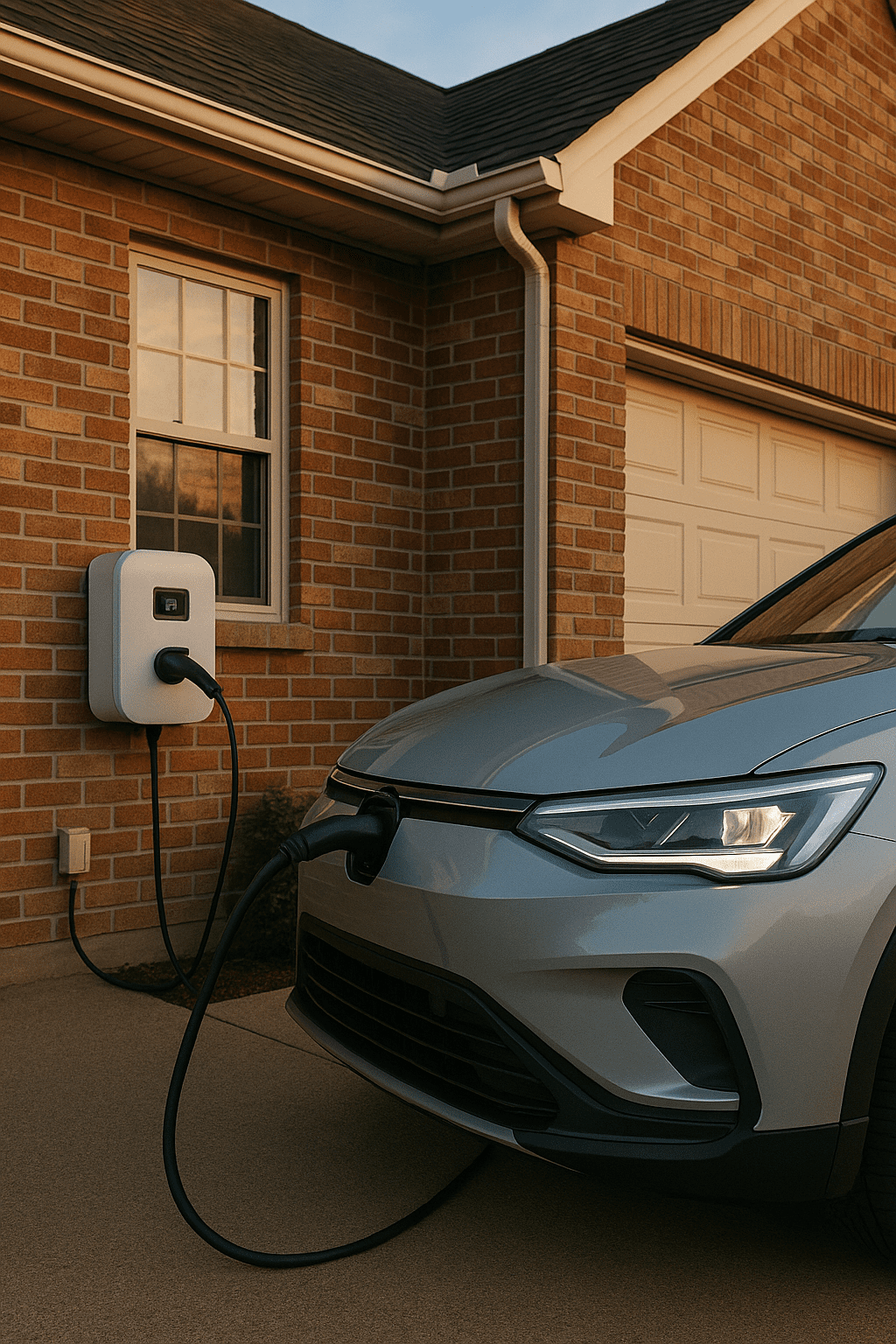

What happens when your car becomes a two-way power station? I tested it for three months to find out.

So last week, I’m having coffee with my neighbor Tom—the guy who’s always got an opinion about everything—and he notices this weird box installed next to my garage. “What the hell is that thing?” he asks. “Solar inverter or something?”

“Nah,” I tell him. “It’s a bidirectional charger. My car can power the house now.”

He gives me that look. You know the one. The “you’ve finally lost it” look. “Your car… powers your house. Like, your electric car. Charges your house. Instead of the other way around.”

“Yep. Pretty wild, right?”

He’s still processing this when the lights in my garage flicker on—running off the Nissan Leaf sitting in my driveway. That’s when I saw it click. The moment he realized this isn’t some sci-fi concept anymore. It’s happening right now, in my completely ordinary suburban driveway.

Vehicle-to-Grid technology—or V2G if you want to sound less nerdy at parties—has been this thing people talk about for years. Always “coming soon.” Always “just around the corner.” But here’s what nobody tells you: it’s actually here. Not everywhere, and not perfect, but real enough that I’ve been living with it for three months now.

And you know what? It’s weird. It’s occasionally frustrating. It’s definitely not plug-and-play yet. But it’s also kind of amazing when it works. Let me walk you through what I’ve learned, because the reality is way more interesting than the hype.

How Vehicle-to-Grid Actually WorksEV Battery

60-100 kWhBidirectional

Charger/Inverter

Converts DC ↔ ACYour HomePower Grid

(Optional Connection)

DC Power

AC Power

Sell to Grid

Energy flows both ways: Grid/Battery → Car for charging | Car → Home/Grid for power backup or earnings

What Vehicle-to-Grid Actually Means (Without the Corporate Buzzwords)

Okay so first, let me clear up what this technology even is, because there’s a lot of terminology floating around that makes it sound more complicated than it needs to be.

Normally, when you plug in your EV, electricity flows ONE way. From the grid (or your home’s electrical system) into your car’s battery. Charging. Simple. That’s what we’ve all been doing since EVs became a thing.

Vehicle-to-Grid flips that around. Or more accurately, it makes it work BOTH ways. Your car can still charge normally, but now it can also push electricity back OUT. Back to your house. Back to the grid. Wherever you need it to go.

Think of your EV as basically a giant battery pack on wheels. Most electric cars today have somewhere between 60 and 100 kilowatt-hours of storage. Some trucks, like the Ford F-150 Lightning, have even more—up to 131 kWh in the extended range version. That’s a LOT of stored energy. Way more than those portable power stations people buy for camping or emergencies.

So the idea is: why not use that massive battery for more than just driving? When the car’s parked in your garage (which is like 95% of the time for most people), that energy is just… sitting there. Vehicle-to-Grid technology lets you tap into it.

The Different Flavors of Bidirectional Charging

Here’s where it gets a bit alphabet soup-y, but stick with me because these distinctions actually matter.

V2G (Vehicle-to-Grid): This is when your car feeds electricity directly back to the utility grid. The big kahuna. The most complex setup. But also potentially the most lucrative because you can actually sell power back to the utility during peak demand times.

V2H (Vehicle-to-Home): Your car powers your house, but it’s not connected to the broader grid. This is more common right now because it’s simpler to set up. When the power goes out, your car keeps your fridge running, lights on, maybe even the AC if you’ve got enough juice.

V2L (Vehicle-to-Load): This is the most basic version. Your car has outlets—just regular 120V plugs—and you can power individual devices or tools. Like using your car as a generator for a camping trip or a job site. A bunch of new EVs have this feature built in.

What I have at my house is technically V2H with the capability to do V2G once my utility finishes their pilot program paperwork. Which, knowing how utilities work, could be next month or next year. Bureaucracy moves slow.

Why Would Anyone Actually Want This?

When I first heard about V2G a few years ago, I thought “okay, cool concept, but who cares?” Like, my car charges at night, I drive during the day, everything works fine. Why complicate it?

Then we had a power outage last winter. Not a quick one either—one of those multi-day blackouts because a storm took out transmission lines. My neighbor with the diesel generator kept us updated on how much fuel he was burning through. Another neighbor drove to three different gas stations looking for ice to save their food.

And me? I plugged my fridge into my car. Ran some lights. Charged our phones. Kept the heat running at a low level. Didn’t solve everything, but we were comfortable while half the neighborhood was scrambling.

That’s when it clicked. This isn’t just some cool tech toy. It’s actually useful. Here’s why people are getting interested:

Backup Power That’s Actually There When You Need It

Remember I mentioned that F-150 Lightning with 131 kWh? Ford claims that can power an average American home for THREE DAYS. Even my modest Nissan Leaf with 62 kWh can run my house for about a day and a half if I’m careful about what I’m using.

Compare that to a typical home backup generator. Those usually run on propane or natural gas, and you’ve got to maintain them, test them regularly, and hope they actually start when you need them. With an EV, the “generator” is something you use every single day. You KNOW it works.

Plus, it’s silent. No engine rumbling at 3 AM. No exhaust fumes. Just quiet, clean power coming from your driveway.

Power Outage: Traditional Home vs. V2G-Equipped Home

❌ No Power

Dark, cold, food spoiling⚡ GRID DOWN

EV

✓ V2G Powered

Lights on, fridge running!

Real Story: During last winter’s outage, my V2H system kept essentials running for 36 hours

while neighbors scrambled for gas generators. No noise, no fumes, no stress.

The Money Angle (Which Is… Complicated)

This is the part that gets people excited, but I’m going to be real with you: the “make money from your car” thing is not as straightforward as some articles make it sound.

The idea is that utilities will pay you to use your car’s battery during peak demand times. Like on a hot summer afternoon when everyone’s running their AC and the grid is stressed. Instead of firing up expensive and polluting “peaker” power plants, the utility could pull power from thousands of parked EVs.

There was this pilot program in Denmark that people love to cite—participants earned about €1,300 ($1,500 USD) per year per car. Sounds amazing, right? But here’s what those articles don’t mention: those were commercial fleet vehicles specifically dedicated to the program. They were plugged in and available basically 24/7. The owner wasn’t driving them to work every day.

For regular people like you and me? The earnings potential is… less clear. My utility (in California) has a pilot V2G program I’m trying to join, and their projected payments are more like $400-600 per year. Still nice! But not “quit your day job” money.

That said, even without direct payments, there’s this concept called “time-of-use arbitrage” which is a fancy way of saying: charge when electricity is cheap, discharge when it’s expensive. If you’re on a time-of-use rate plan, your electricity might cost 12 cents per kWh at night and 40 cents during peak hours. If you can charge at night and run your house during peak times, you’re essentially “making” 28 cents per kWh you cycle through.

Over a month, that adds up. Is it lifechanging money? No. But it takes the sting out of the EV’s charging costs and might even make the car net-positive on electricity.